- Home

- Types of Goals

- Everest Goals

Everest Goals: What Happens When You Set Magnanimous Goals That Truly Inspire You?

Not all goals are created equal. Everest goals are the future of goal setting.

Some goals help you get things done—pay the bills, get to the gym, answer the emails.

Other goals? They call on your strengths. They awaken you. They lift your mood, your mindset, even your sense of meaning.

We call these Everest Goals— because they aim for a peak. This doesn't mean they are large necessarily. It can refer to their virtuousness, to how they matter deeply, and to the catalyst they ignite and how they help you grow.

Let’s explore how to move your everyday goals a little closer to your own “Mini Everest.”

What Is an Everest Goal, Really?

The term comes from the work of researcher Kim Cameron, who studied what happens when people and organizations aim for their own version of “Mount Everest”—goals that are deeply meaningful, energizing, and designed to bring out our best (Cameron, 2012).

They’re about aiming for something in a certain way based on a collection of research from the field of positive leadership. Cameron identified five key ingredients that make goals into Everest goals.

Let’s look at those now.

Attribute 1. Goods of First Intent - They Matter Because They Matter

Everest goals are meaningful in and of themselves. You're not doing it for a bonus or because someone told you to. You're doing it because it feels right, important, or true to who you are.

Researchers sometimes call these “goods of first intent,” based on the work of Aristotle. Just think of it like this: you're not doing it to get somewhere—you’re doing it because it’s worth doing in and of itself (Cameron, 2013).

According to Aristotle, examples of goods of first intent (or intrinsic goods) include:

-

Eudaimonia (often translated as flourishing or human well-being)

– The highest good for humans, according to Aristotle. It’s not a fleeting feeling of happiness, but a life well-lived, fulfilling one’s potential in line with virtue. -

Virtue (e.g., courage, generosity, honesty)

– Practicing virtue is not just a means to earn praise or rewards; it’s part of living a meaningful and excellent life. -

Friendship

– Especially deep, virtuous friendship. These are valued not for utility or pleasure alone, but because the relationship itself is meaningful and fulfilling. -

Contemplation and Wisdom

– The life of the mind, especially philosophical contemplation, was seen by Aristotle as one of the highest forms of human activity, valuable in itself.

Quote from Nicomachean Ethics (Book I, Chapter 7):

“We call final without qualification that which is always desirable in itself and never for the sake of something else. Happiness [eudaimonia], above all else, is held to be such an end.”

So, in short: goods of first intent are things we do or pursue because we believe they are inherently worthwhile, not because of what they’ll get us.

Attribute 2. Intrinsically Valuable - Spark Lasting Energy From Within

Everest Goals aren’t just exciting on the surface — they light a spark that keeps going. That’s because they connect to intrinsic motivation — the kind of motivation that comes from doing something you genuinely care about and freely choose (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

When I coach, one of my main goals is to help you discover and commit to something your mind and body naturally resonate with—a goal that feels right, energizing, and freely chosen, with minimal inner resistance. I bring my knowledge, skill, and experience to support that process.

If you're curious about what this could look like for you, book a free coaching consultation.

These goals aren’t driven by pressure, rewards, or ticking boxes. Instead, they feel naturally energizing and meaningful.

When goals align with what matters to us and we feel ownership over them, our energy becomes more sustainable. We're more likely to stay engaged, productive, and proactive.

Research shows that motivation can be boosted or drained by our environment, so creating conditions that support inner drive helps these goals stick — and thrive (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

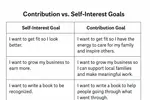

Attribute 3. Contribution Goals - Make it About More Than Just You

Everest Goals aren’t just about personal gain — they’re about making a positive difference. While it’s natural to want success for ourselves, goals that focus on contributing to others often go further.

Whether it’s helping your family, supporting a team, or improving your community, contribution-based goals lead to stronger relationships, more trust, and even better mental health (Crocker & Canevello, 2008; Niiya & Crocker, 2008).

Over time, these kinds of goals tend to help people grow, while purely self-focused goals can create pressure to prove your worth, which takes a toll on wellbeing (Crocker & Park, 2004).

Even in later life, people who focus on giving rather than receiving support tend to live longer (Brown et al., 2003).

Shifting from “What do I get?” to “What can I give?” can unlock surprising benefits — both for others and for yourself.

Want to dive deeper into this topic? Read more about the power of contribution goals here.

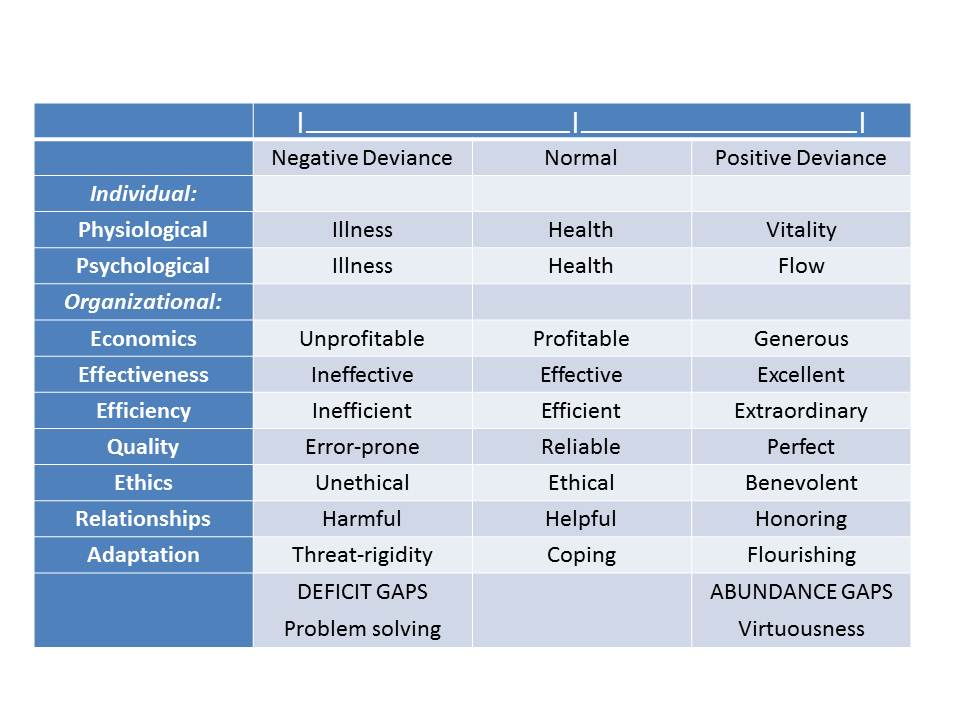

Attribute 4. Positive Deviance - Reaching for the Remarkable

One of the standout features of an Everest goal is that it’s not just a bit better than what’s typical — it reaches for something extraordinary.

In academic terms, Kim Cameron called this positive deviance, but a more down-to-earth way to think of it is going beyond the norm— aiming for truly exceptional outcomes (Cameron, 2012).

Think for example - deeply respecting and treasuring employees rather than just giving them the bare minimum required by law.

You can see this illustrated in both individuals and organisations. Below are a few examples:

For example, instead of simply managing stress (which might be considered “normal” psychological health), someone might pursue a lifestyle that allows them to regularly experience flow — that state of deep focus and enjoyment.

Or in a workplace, a team might not just work efficiently, but become a place where people flourish, collaborate exceptionally well, and deliver results beyond expectations.

These kinds of goals stretch what seems possible. They invite innovation, surprise, and a level of success that might feel “off the charts.” That’s part of the magic.

Attribute 5. Affirmative Orientation - Focus on What’s Possible

Everest Goals don’t just fix what’s broken — they imagine what could be great.

This is what psychologist Kim Cameron calls having an affirmative orientation: a way of thinking that turns “What’s wrong?” into “What’s possible if things go really well?” (Cameron & Spreitzer, 2011).

Instead of settling for the minimum or staying in survival mode, these goals aim for flourishing — even in the face of challenges. This doesn’t mean ignoring problems, but it does mean choosing to build hope, energy, and momentum to accomplish remarkable things.

Research shows that this kind of thinking supports optimism, resilience, and a sense of meaningful progress.

At its heart, an affirmative approach believes in the potential for better — and that belief changes everything.

Moving Your Goal a Little Closer to Everest

Not every goal needs to be world-changing. But when you give your goal even a bit more meaning, a bit more positivity, or a bit more alignment with your values, something starts to shift.

You feel more engaged. You remember why you care. You make bolder choices. You surprise yourself.

Affiliate products.

In my articles I occasionally recommend products that I believe will enhance your goal setting journey. If you buy something through one of those links, I receive a small commission. There is no additional cost to you. To learn more, please see my affiliate disclosure document.

References

Brown, S. L., Nesse, R. M., Vinokur, A. D., & Smith, D. M. (2003). Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: Results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychological Science, 14(4), 320–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.14461

Cameron, K. S. (2012). Positive Leadership: Strategies for Extraordinary Performance. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. Link.

Cameron, K. S. (2013). Practicing Positive Leadership: Tools and Techniques That Create Extraordinary Results. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. Link.

Cameron, K. S., & Spreitzer, G. M. (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship. Oxford University Press. Link.

Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2008). Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: The role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.555

Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2004). The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 392–414. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.392

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. Springer. Link.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The "what" and "why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Niiya, Y., & Crocker, J. (2008). Compassionate and self-image goals in the United States and Japan. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39(3), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022112451053

- Home

- Types of Goals

- Everest Goals

Who I'm Affiliated With

I'm proud to be part of professional networks that value evidence-based practice, inclusion, and social impact.