- Home

- Types of Goals

- Contribution Goals

Contribution Goals: The Shift That Changes Everything

When most people set goals, they focus on what they want. A better job. A healthier body. A finished project. A sense of achievement. These are important — and completely natural. But there's another way to think about goals — one that shifts your entire experience of pursuing them.

That shift is toward contribution.

What is a Contribution Goal?

Contribution goals are goals focused on creating a positive impact beyond yourself. They aim not only to benefit you, but also to support, uplift, or improve the lives of others.

Rather than asking, “What do I want to achieve?”, contribution goals ask:

“How can I make things better — for others, and myself?”

This doesn’t mean you need to give up your own desires. The power of contribution goals is that they still involve your personal growth and success — but with an outward ripple.

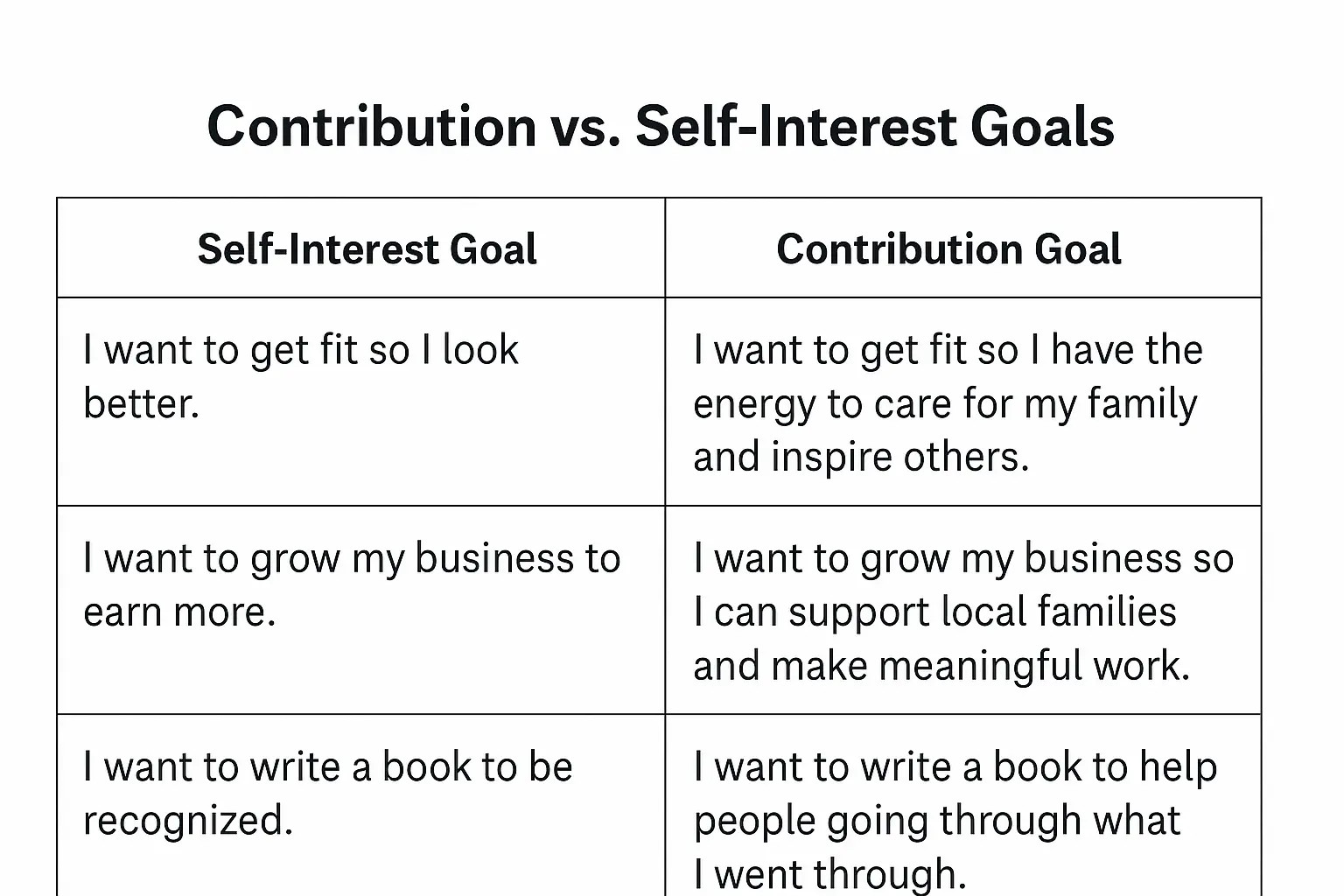

Contribution vs. Self-Interest Goals: What’s the Difference?

Let’s take a closer look at the contrast.

The same goal can live in either category. It’s the orientation that changes it.

And this shift in orientation isn’t just philosophical — it has real, measurable effects on wellbeing.

Why Contribution Goals Matter More Than You Might Think

Research shows that how we frame our goals affects more than just our outcomes — it affects our health, our relationships, and even how long we live.

1. Less Burnout, More Sustainable Motivation

Self-interest goals often carry a hidden emotional load. We want to prove something. We want to be worthy. We want to feel “enough.” And when things go wrong, it hits hard.

This dynamic of proving yourself is linked with anxiety, perfectionism, and burnout. (Crocker & Park, 2004).

In contrast, contribution goals shift the focus. The goal isn’t to prove you’re worthy — it’s to make a difference.

That change in intention keeps self-worth out of the picture, which protects your energy and resilience. You’re more likely to stay motivated, even when things get tough, because it’s not about you — it’s about the impact.

2. Better Relationships and More Trust

A series of studies by Niiya and Crocker (2008) found that people who pursued compassionate goals (a type of contribution goal) had:

- Closer friendships

- Greater trust in others

- More social support

Similarly, Crocker and Canevello (2008) showed that contribution-focused goals led to stronger feelings of connection, cooperation, and understanding.

When we orient ourselves toward giving, people feel it — and they respond in kind. The result is a social environment of mutual support, rather than competition.

3. Greater Psychological Growth

Contribution goals activate what researchers call a growth orientation — a mindset focused on learning, expanding, and evolving. Self-interest goals, by contrast, often trigger a proving orientation — a need to validate yourself or perform for others.

Over time, a growth orientation leads to greater adaptability, mental flexibility, and long-term wellbeing. The proving orientation? It might lead to short-term performance, but it also increases stress and makes people more reactive to failure.

4. Even Physical Health Benefits

The benefits of contribution run deeper than just mindset. In one study (Brown et al., 2003), older married adults who provided support to others were more likely to live longer than those who simply received support. The act of giving is itself life-giving.

All Goals Can Become Contribution Goals

Here’s the exciting part: you don’t have to abandon your goals to benefit from this. You simply need to look at them through a different lens.

Ask yourself:

- How does this goal benefit others — directly or indirectly?

- How can I expand this goal’s impact?

- Who else might be affected by my success?

- What’s the ripple effect?

This process doesn’t diminish your ambition — it deepens it.

✨ From Self-Centered to Contribution-Centered: A Subtle Shift with Huge Impact

Here’s something that might surprise you: starting with contribution doesn’t narrow your goals — it actually expands them.

When you lead with the difference you want to make, instead of focusing first on what you need or want, new ideas and possibilities start to open up. The contribution becomes your fuel — and suddenly, there are more ways to move forward, more ways to feel energized, and more ways to succeed.

Let’s look at what happens when you flip the order and make contribution the starting point.

Let’s revisit those examples in this new light:

Original contribution re-phrasing:

- “I want to get fit so I have the energy to care for my family and inspire others.”

Contribution-first reframing:

- “I want have the energy to care for my family and inspire others ”

Now, instead of narrowing the focus to getting fit as the only route, the door opens to:

- getting better sleep

- improving diet

- reducing screen time

- setting boundaries

- rethinking your work structure

- and getting fit

All because the central focus is on who you're showing up for, not what you're escaping from.

Original contribution re-phrasing:

- “I want to grow my business so I can support local families.”

Contribution-first:

- “I want to support local families.”

This invites action way beyond just growing your business:

- volunteering

- hosting a party

- offering workshops

- becoming an advocate or mentor

- and growing your business

Now the goal isn’t confined to one path; it becomes a mission with many access points for meaning and motivation.

The original goal may still be accomplished — but it’s now one of many ways to contribute.

🎯Why This Works

Starting with contribution first:

- Expands your creative problem-solving. You no longer fixate on one rigid route.

- Energizes you more deeply. You tap into meaning and purpose, which research shows fuels sustainable motivation.

- Decouples your self-worth. It becomes about service, not status.

- Grows your identity. You’re not just a goal-achiever — you’re a difference-maker.

How to Set a Contribution Goal

Start With What Matters to You

Think about causes, people, or situations that tug at your heart. What do you care about? Who do you want to help?

Choose a Goal That Connects

This can be a direct service (e.g., mentoring), or something that has ripple effects (e.g., parenting with more compassion, or creating a product that solves a problem).

Name the Contribution

Be explicit. Define how the goal will benefit others — and why that matters to you.

Link It to Action

Make the goal tangible and actionable. It could be daily, weekly, or monthly. For example:

- “Share one useful resource a week to help people in my industry.”

- “Speak kindly and constructively to each student in my class today.”

- “Design my workday around ways to ease stress for my colleagues.”

Reflect Often

Ask: How did I contribute today? What effect did it have? What does that tell me about what’s meaningful?

Contribution Goals in Coaching and Life Design

In coaching sessions, people often feel stuck when their goals are tightly bound to self-worth. The inner dialogue becomes:

“If I fail, I’m a failure.”

“If I don’t reach this, I’m not good enough.”

But when we zoom out and ask, “What positive impact could this goal have on others?”, something shifts. Pressure softens. Energy rises. Meaning grows.

In fact, contribution is one of the most powerful tools for breaking through the inertia of self-doubt. It invites people to move — not to prove they’re worthy — but because they already are.

Final Thoughts: Contribution Isn’t Self-Sacrifice

Let’s be clear: contribution goals are not about neglecting your own needs. They’re about expanding your intention to include others.

The best contribution goals are the ones where you win and others win too. The more energized, clear, and fulfilled you are, the more you have to give.

So whether you’re setting a small habit or a big bold goal, ask:

“How can this be a gift — not just to me, but to the world around me?”

References

Brown, S. L., Nesse, R. M., Vinokur, A. D., & Smith, D. M. (2003). Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: Results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychological Science, 14(4), 320–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.14461

Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2008). Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: The role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.555

Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2004). The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 392–414. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.392

Niiya, Y., & Crocker, J. (2008). Compassionate and self-image goals in the United States and Japan. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39(3), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022112451053

- Home

- Types of Goals

- Contribution Goals

Who I'm Affiliated With

I'm proud to be part of professional networks that value evidence-based practice, inclusion, and social impact.